Think about your favourite computer game. Are you a pirate? A ninja? Maybe a starship captain or a mystical sorcerer? And are you the kind of hero who rushes fearlessly into danger, or bides their time then executes a flawless plan?

If you take any game and strip away the “playing” part — whether its collecting coins or exploding alien ships — you’re left with a story. Rather, you’re left with many stories. One of the cool parts about digital games is that they’re interactive. Our choices guide the story and lead us to different endings.

Of course, its not as simple as choosing between a handful of pre-written adventures. Sometimes players can jump between storylines, or return to a previous part of the adventure. Other times they’ll pass a point of no return (finding a secret key, revealing a villain) and it wouldn’t make sense to go back.

This makes interactive stories tricky to write. How do developers keep track of everything?

FINITE STATE MACHINES

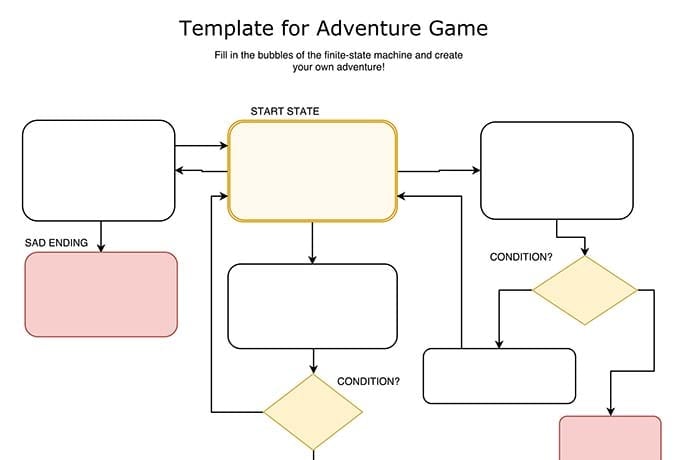

One simple method is to model a game’s storyline with finite state machines. In some sense, a finite-state machine (FSM) is a glorified flowchart. For example, if you were creating an adventure game, your FSM might look something like the chart on the next page

The elements of the chart are:

States. These are the big building blocks of the game — anything that moves the story forward or changes the nature of the adventure. In the example, the states are mostly locations: the crystal cave, the underground river. States can be events, such as finding the magic flute, or meeting. The start state is marked in beige.

Transitions. The game is played by jumping from state to state using transitions, shown as arrows. If the player chooses ‘left’ in the ‘Start State’, they move to the Crystal Cave. Notice how some transitions can only be made under certain conditions. For example, a player can’t jump from ‘Underground River’ to ‘Dragon’s Lair’ if they don’t have the rope.

End States. Certain states end the game. Some are happy endings (shown in green), and others are less happy (shown in red). This example only has one happy ending, but there can be as many as you want! Maybe you could add a scenario where you befriend the dragon roast marshmallows together?

A developer could easily add some gameplay on top of the basic model. Maybe they’d add some monsters to fight or some puzzles to solve. This extra gameplay doesn’t change the story; it just makes the process a little more exciting.

The beauty of finite state machines is that they’re easy to visualize, understand, and analyze. In this case, we’re using them as an organizational tool for a story. But if you were in a math mood, you could represent all the elements — states and transitions — using symbols. Imagining a program as a state machine can make things easier when coding big projects. States can be used to keep track of variables, like what objects you have, what characters you can talk to, and what locations you can visit.

In the diagram, conditions are shown using triangles. Real FSM don’t have this extra element; the conditions are contained implicitly within the transitions. But showing the conditions separately does make the flowchart easier to follow!

CREATE YOUR ADVENTURE!

This summer, challenge yourself by creating your own story, modelled using an FSM! It can be simple; just copy the above template and fill it in with your own ideas. Or, write something as grand and convoluted as a novel!

THE STEPS

Brainstorm ideas. Is your story a submarine escapade? A time travelling adventure with dinosaurs?

Think up endings, happy and / or sad. Because once you know the beginning and the ending, it’s easy to connect them.

Add obstacles. What are the key elements your players will have to overcome? Searching for clues and fighting monsters are always a safe bet. Some of my favourite games also include rescuing magical creatures, participating in races, and outwitting villains.

Add detours. A game is no fun if it’s easy to get to the end. Add some detours that complicate the path!

Just keep adding detours; the more the merrier.

TAKE IT TO THE NEXT LEVEL

Remember, our finite-state-machine is a bird’s-eye view of the game — at some point you want to get in there and add the nitty-gritty details. One simple way to do this is to create a choose-your-own-adventure story. In the good ol’ days, these were ink-and-paper books. Each page contained a snippet of text that ended with a series of choices: ‘To drink the potion, turn to Page 93. To eat the cake, turn to Page 7.’ Some of these books would get players to flip coins or roll dice in order to add some randomness.

And while there’s nothing wrong with pen and paper, nowadays there’s lots of cool online software that does the organization process for you.

INKLEWRITER

http://www.inklestudios.com/inklewriter/

Inklewriter is all about interactive stories; not so much about other game elements. The beauty of inklewriter is that it’s really easy to connect different states and change things as you go.

QUEST

http://textadventures.co.uk/quest

While Quest does help you make choose-your-own-adventure stories, it also allows you to make text-based games like Zork. Long story short, you can add a little bit of gameplay. Nothing fancy —mostly just text commands like “take”, “drop”, “examine”, or “attack”. But it’s a step above flipping between pages.

TWINE

https://twinery.org/

Similar to inklewriter, except that Twine uses a ‘sticky note format’ to organize your states (or pieces of the story). It’s recommended that you have a good outline before getting started, since organizing the states together can get complicated. But since you’re modelling everything using an FSM, that shouldn’t be a problem, right?

Now pick your favourite platform and go make a game!